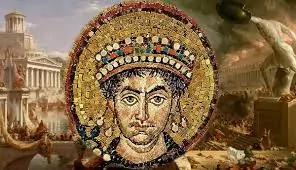

Although he is largely forgotten today, the sixth-century Roman Emperor Justinian’s legal code has had a remarkable reach and influence, even on American law.

It was Roman law that gave Europe and the Americas that uniform machinery of justice. According to historian Robert Byron in his monumental 1929 book The Byzantine Achievement, “Let it simply be borne in mind that those principles of justice which form the basis of society in twentieth-century France or Scotland, were formerly as deeply engrained in the subjects of the Greek Empire as in the inhabitants of those countries today.”

That may be why Justinian’s code was so highly valued among America’s Founding Fathers.

On October 5, 1758, over twelve hundred years after Justinian’s Body of Civil Law first appeared, a young law student in Braintree, Massachusetts, named John Adams wrote in his diary: “I am this Day about beginning Justinians Institutions with Arnold Vinnius’s Notes. I took it out of the Library at Colledge.”

Adams noted down frankly that he hoped by studying this thousand-year-old but enduringly relevant legal text that he would gain an advantage over his fellow students: “Let me be able to draw the True Character both of the Text of Justinian, and of the Notes of his Commentator, when I have finished the Book. Few of my Contemporary Beginners, in the Study of the Law, have the Resolution, to aim at much Knowledge in the Civil Law. Let me therefore distinguish myself from them, by the Study of the Civil Law, in its native languages, those of Greece and Rome.”

Adams worked assiduously, writing that same day: “I have read about 10 Pages in Justinian and Translated about 4 Pages into English. This is the whole of my Days Work. I have smoaked, chatted, trifled, loitered away this whole day almost.” [Spelling as in the original.]

John Adams was a remarkable man. The prospect of a contemporary law student working painstakingly through an ancient Latin-language legal text is virtually inconceivable. But it is important to note that Adams wasn’t doing this to show off his scholarly erudition; he was studying Justinian in order to master the intricacies of civil law as it was applied in colonial America over a millennium after Justinian. And Adams, of course, was one of the foremost architects of the American legal system that, up until the faddish popularity of Critical Legal Studies and other legal and cultural fashions of our day, was renowned the world over for its capacity to secure the guarantee of equal justice for all, regardless of their wealth or social status.

Nor was Adams alone in his regard for Justinian’s legal code. In 1783, James Madison, the foremost framer of the US Constitution, drew up a list of books he believed must be included in a Library of Congress; it included Justinian’s Body of Civil Law. Thirty years later, in 1814, Thomas Jefferson, having retired from the presidency five years before, gratefully acknowledged receipt of an English translation of Justinian’s Institutes, which had been sent to him by its translator, Thomas Cooper. In the course of his letter to Cooper, Jefferson referred to Blackstone’s commentaries, as [grammar and punctuation as in the original] “correct in it’s [sic] matter, classical in style, and rightfully taking it’s [sic] place by the side of the Justinian institutes. but like them, it was only an elementary book.”

It was the modern unmooring of the American legal code from these traditional foundations that allowed the left to corrupt our justice system and remove from it the ideas of blind justice and the equality of rights of all people before the law. Legal faddism, and above all the abandonment of the idea that the actual words of the law mattered in how that law should be interpreted, as opposed to its being interpreted in accord with the spirit of the age and the political proclivities of the judges, has had a devastating effect on the integrity of American law. A return to its foundations in the work of Justianian and other legal giants would do us a world of good.

The left, of course, has far too much of its program tied up in the idea that literal interpretation of laws is some hidebound, antiquated and counterproductive process ever to go for the idea that a return to traditional legal interpretation would be salutary. And that’s precisely the problem.