The Supreme Court Can’t Stop Trade Rebalancing — Even if It Tries

The legal establishment in Washington has convinced itself that the Supreme Court is about to ride to the rescue of the global trade status quo. Lawyers at white-shoe firms are telling their multinational clients to hold tight: the courts will strike down the President’s tariffs under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), and the whole trade rebalancing project will collapse.

They’re wrong. Not because the Justices won’t strike down the tariffs. They might. But because the administration has a path forward that doesn’t depend on tariff authority at all, one that rests on powers the statute expressly grants in plain English, and one that may actually be more effective than tariffs at forcing surplus countries to the table.

Here’s the thing the trade establishment doesn’t want to think about: IEEPA doesn’t just let the president regulate imports. It lets him prohibit them. And it lets him issue licenses as exceptions to that prohibition. Those aren’t implied powers or creative readings. They’re right there in the text of the law: the president may “prevent or prohibit” importation and may act “by means of instructions, licenses, or otherwise.”

That language points to a mechanism that could reshape the global trade landscape even if every tariff the administration has imposed gets struck down tomorrow.

President Donald Trump holds up a display of reciprocal tariff rates during his “Liberation Day” event in the White House Rose Garden on April 2, 2025, in Washington, DC. (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Warren Buffett Had the Right Idea

The concept isn’t even new. Back in 2003, Warren Buffett proposed an import certificate system in the pages of Fortune magazine. Buffett’s insight was that persistent trade deficits represented a slow transfer of American wealth to foreign hands — what he called a national “squandering” of assets — and that the solution was to require certificates that authorized importation.

Buffett’s version would have issued certificates to American exporters, who could then sell them to importers on a secondary market. The idea attracted bipartisan interest — Senators Byron Dorgan and Russell Feingold introduced the Balanced Trade Restoration Act of 2006 based on the concept, but it never made it to a vote.

The proposal described here — call it I-ACES, the Import Authorization Certificate Exchange System — takes Buffett’s core insight and improves on it in a critical way. Instead of creating a domestic market in certificates between American exporters and importers, I-ACES sells the certificates directly to foreign governments. That single change solves the political problem that has dogged the tariff debate from the beginning.

Foreign Governments Pay, Not Americans

For years, critics of the administration’s trade program have hammered one talking point above all others: “Americans pay the tariffs, not foreign countries.” Set aside that this claim has been badly undermined by the actual data; import prices have not surged the way the models predicted. The deeper problem with the critique is political, not empirical. It gives opponents a simple, repeatable line that resonates even when it’s misleading.

I-ACES eliminates that line of attack entirely.

Under this system, Treasury offers to sell Import Authorization Certificates directly to the governments of countries running bilateral trade surpluses with the United States. The purchase price equals a percentage — 20 to 50 percent — of the country’s prior-year bilateral surplus. The foreign government pays Treasury. That’s the transaction. There is no ambiguity about who is writing the check.

Take Germany. Assume Germany exported $150 billion to the United States last year and imported $100 billion from us, running a $50 billion surplus. Under I-ACES, Treasury offers Germany’s government certificates authorizing imports for one year. At a 20 percent rate, the price is $10 billion — paid by the German government to the United States Treasury.

Germany then has three choices. Pay for continued access. Accept the loss of access to U.S. markets. Or open its market so that its people start buying more American goods to shrink the surplus and lower the certificate price in future years. Every one of those outcomes is a win for the United States. And in every scenario, it is the foreign government making the decision and bearing the cost.

Here’s the part that makes I-ACES elegant in its simplicity: the United States doesn’t care how a foreign government pays for its certificates or how it distributes them.

Maybe Germany charges its exporters directly, passing along the cost of market access. Maybe it funds the purchase through general tax revenue. Maybe it borrows the money. Maybe it auctions the certificates to its own exporters and lets the market determine allocation. Maybe it subsidizes its most strategic industries and makes the rest fend for themselves.

That’s entirely a matter of sovereign discretion. The U.S. transaction is clean: Treasury sells certificates to a foreign government, the foreign government pays. What happens on the other side of that transaction is that country’s domestic policy choice. The United States sets the terms of access. Foreign governments decide how to meet them.

This is a feature, not a bug. It means the U.S. government doesn’t have to design or administer a complex allocation system. It doesn’t have to pick winners and losers among foreign industries. It doesn’t have to monitor how certificates are distributed or fight about pass-through rates. One transaction per country per year. The rest of the world decides how and to whom the export licenses are distributed domestically.

The Legal Dilemma the Critics Can’t Escape

Now, the inevitable objection: isn’t this just a tariff by another name?

Fortunately, that’s not an objection that the federal courts will be able to make if they knock down the IEEPA tariffs as a tax unauthorized by the statute. The Trump administration argued that the plain language authorizing an import ban and licenses should also allow for a tariff as a lesser restriction. If the court rejects this because it insists on the legal gravity of a distinction between licenses and tariffs, it cannot then turn around and say the licenses are effectively tariffs.

In other words, a court that insists on the distinction between a ban-and-license regime and tariffs cannot also claim the licenses are tariffs.

Trade Negotiation Over License Prices Rather Than Tariffs

The price of the licenses can be negotiated just as the tariff levels have. If a country agrees to make joint-venture-like investments in the U.S., perhaps it gets a lower license fee. If it insists on buying Russian oil, the license fee goes up. All of the leverage the Trump administration has achieved through tariff diplomacy is still available through import license diplomacy.

I-ACES also dramatically simplifies enforcement. Instead of checking prices on millions of imported goods and assessing tariffs, you have one number per country per year. Customs and Border Protection simply checks to see if the country has purchased an import license. The Commerce Department assesses the prices of the I-ACES license by looking at the amount of the country’s trade imbalance, based on a calculation it already performs each year. That’s cleaner than anything in the current tariff system.

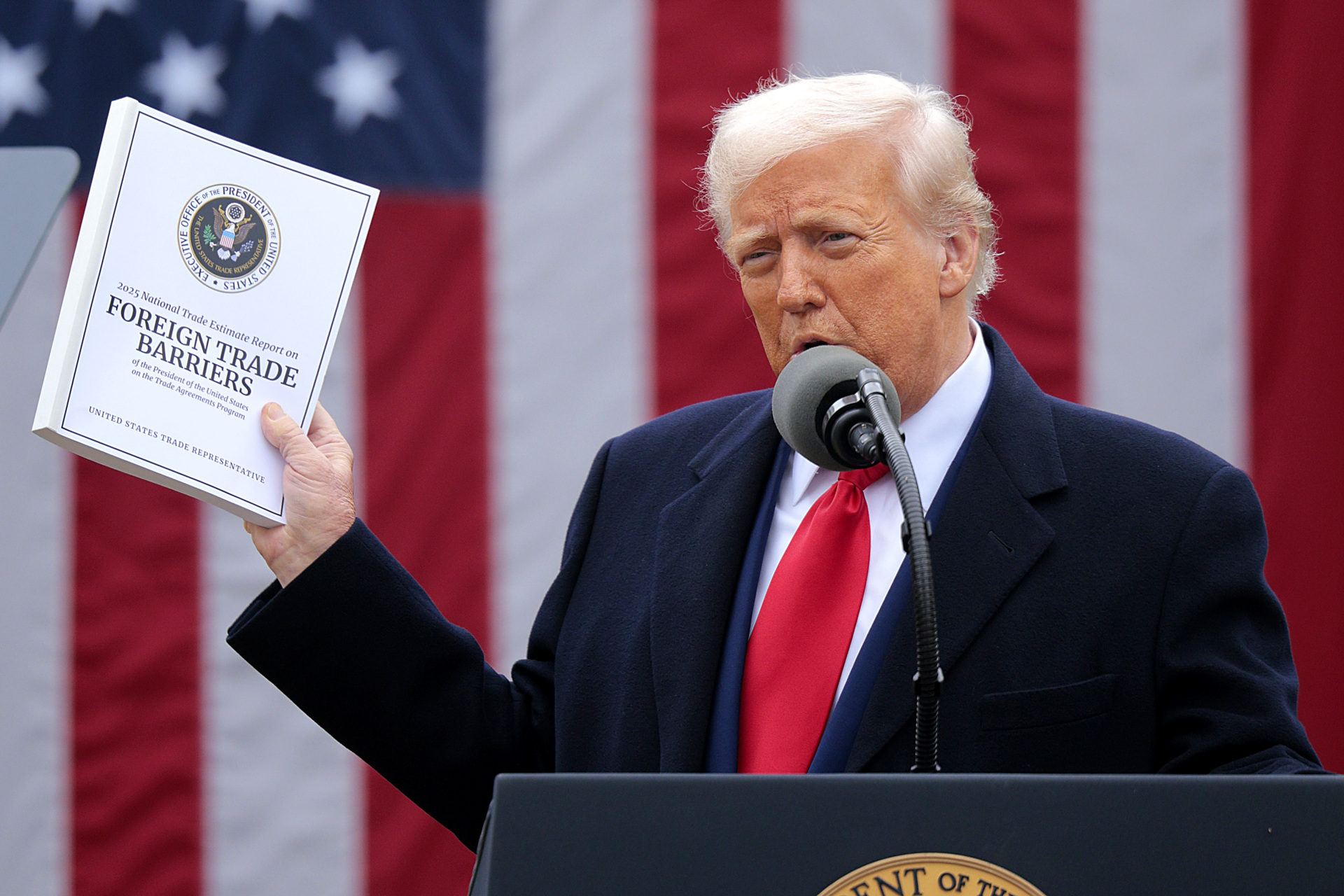

President Donald Trump holds up a copy of a 2025 National Trade Estimate Report as he speaks at the “Liberation Day” event in the White House Rose Garden on April 2, 2025, in Washington, DC. (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

The broader point is one the legal and economic establishment has consistently failed to grasp throughout this administration’s trade program. The persistent bilateral trade deficits the United States runs with dozens of countries are not natural features of a healthy global economy. They represent decades of institutional and policy choices by surplus countries — currency management, industrial subsidies, market barriers — that have systematically transferred income and productive capacity out of the United States. Buffett saw this more than 20 years ago. The economics profession mostly shrugged.

Standard economic theory says these imbalances should self-correct. Deficit countries should eventually run surpluses as the accumulated claims get spent. In practice, that correction has never come. China, Germany, Japan, Vietnam, and others have maintained enormous surpluses with America for decades. When economists are called upon to explain this persistent violation of economic theory, the response has been a shrug.

The Administration is not shrugging. And if the Supreme Court takes away one tool, the statutory text provides another. The lawyers and economists who are counting on the courts to restore the old order should prepare themselves for disappointment. The president has more options than they think, and the law is clearer than they’d like.

President Trump is holding an ace in his hand. If the courts nix the tariffs, he’ll still have the winning trick.