Nyamakop

Nyamakop

Imagine it is 2099 and the Transatlantic Returns Treaty is falling apart as Western museums find ways to wriggle out of promises to return stolen African treasures.

Fed up with the trickery, artefacts expert Prof Grace decides to take matters into her own hands. And the South African knows the perfect people to help: her grandchildren, Nomali and Trevor and her former student Etienne.

In an abandoned warehouse in Johannesburg, Prof Grace sets out her high-stakes plan – to break into museums and private collections and take back artefacts mostly plundered during colonial times.

None of this is real – rather it is the narrative of Relooted, what its creators call an “African-futurist heist game”, released on Tuesday.

But it’s a heist story with a difference – there’s no big pay day at the end of the heist and the characters don’t have a criminal background.

They are motivated not by money – but by ever-shifting goalposts.

The latest amendment to the Transatlantic Returns Treaty means only artefacts on public display have to be returned – and Western museums are now busy wrapping up objects and putting them into storage.

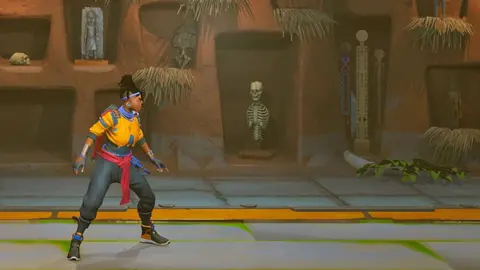

Sports scientist Nomali is the mastermind – and the character through which the game is played, helped by colleagues from across the continent.

“Nomali reluctantly agrees to the first heist to prove how dangerous the whole thing is,” the game’s narrative director Mohale Mashigo told the BBC.

“She would do anything for her family – and she joins them as a way to protect them from themselves and the real danger that is involved in heists.”

Nomali is a parkour legend and uses those skills – running, jumping, climbing, and vaulting over obstacles – to retrieve 70 African sacred and cultural objects.

Her brother Trevor, a locksmith and security systems expert, helps her in and out of the buildings – with intel from The Inside Man, Etienne, who is Belgian-British.

Ndedi, from Cameroon, uses her acrobatic skills for the most elaborate escapes, Cryptic is the hacker from Kenya and Congolese Fred is the getaway driver and gadget maker.

During the twists and turns of the game, other characters emerge.

Relooted is designed by the pan-African team of Nyamakop studio in South Africa.

Its 2018 Semblance debut was the first African-developed game to launch on a Nintendo console.

Designers and voice actors in countries including Nigeria, Angola, Malawi, Ethiopia, Tanzania and Kenya also worked on Relooted.

It is the first of what its CEO Ben Myres hopes will be a line of “African-inspired games for a global audience.”

The action game, which uses motion captures and animated cinematics, is designed for PCs and consoles – which means that it won’t attract many players in Africa, where most people play on smartphones because they are more affordable.

The core target audience is the African diaspora.

Nyamakop

Nyamakop

Sithe Ncube, the game’s project manager, believes it will have a much wider appeal.

“Taking back cultural artefacts that were looted is actually something a lot of people hope for – and fantasise about,” Ncube, who is from Zambia, told the BBC.

Myres came up with the idea for Relooted during a visit to London. His mother had gone to the British Museum, where she saw the Nereid Monument – an ancient tomb that had been dismantled and moved between 1842 and 1844 to the museum, brick by brick, from the south of Turkey.

“She was incensed, just really struck by the audacity of stealing a building and flippantly said: ‘You should make this into a game’,” Myres told the BBC.

Myres substituted buildings for artefacts because “I could never figure out how to make moving a building out of another building very fun.”

In a deliberate contrast to the violent way in which many African artefacts were taken, there’s no violence in Relooted.

Players instead rely on solving puzzles, outsmarting systems, overcoming obstacles, teamwork and athleticism.

“It’s sort of a staging point for where all the artefacts will eventually return to the people they were taken from,” Myres says.

Nyamakop

Nyamakop

The artefacts in Relooted are based on real objects taken mostly by foreigners during the late 19th and 20th Centuries.

Though the game also features more recent thefts – like the sacred vigango carved grave markers from Kenya and Tanzania. A massive demand from Western art dealers encouraged a “theft-to-order” in the 1980s and 1990s – as happened a decade later with Dogon art from Mali.

Also up for grabs by Nomali and her crew is a 300,000-year-old skull found in what is now Zambia.

Kabwe 1, or Broken Hill Man, is one of the most significant human fossils ever found – and has been in the Natural History Museum in London since 1921, when it was discovered.

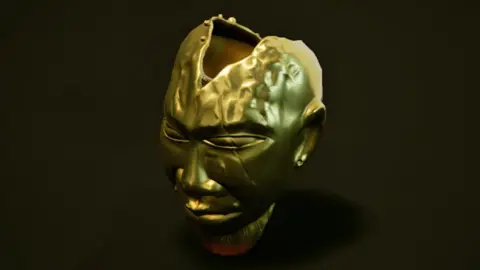

The Asante Gold Mask – which was looted when British troops destroyed the royal palace in Kumasi in 1874 – is now held by the Wallace Collection in London.

The Ngwi Ndem or Bangwa Queen, was removed from Cameroon in 1899. The wooden sculpture was once part of the extensive collection of African artefacts belonging to cosmetics pioneer Helena Rubinstein.

The 81cm (32 in)-tall statute was made into a pop culture icon in the 1930s by renowned artist Man Ray when he photographed it alongside a nude model.

To the Lebang people of south-western Cameroon, the Ngwi Ndem is more than a piece of art. It is a sacred lefem figure that represents the ancestors, symbolises fertility, prosperity and protection and was used in ceremonies.

There’s no sign that the Dapper Foundation in France – which bought it at a Sotheby’s auction in 1990 for $3.4m (£2.5m) – will return it as requested.

Nyamakop

Nyamakop

Formal demands for the return of some of Africa’s best-known artefacts – the Benin Bronzes – were made as early as the 1930s by the Nigerian kingdom’s then monarch, Oba Akenzua II.

He managed to get back two coral bead crowns and a tunic but it was only in 2021 that any significant repatriation of artefacts by Western universities and museums began.

It remains a trickle, however.

Nyamakop co-founder Myres is very clear that Relooted is first and foremost a form of entertainment.

But the South African also sees the game as a “general awareness-raising attempt about African culture, African history, and sort of the scale of this cultural artefact looting that has happened”.

The unique nature of games makes them an ideal vehicle, explains Ncube.

“You must actively engage in games,” she says.

“A lot of interactions are optional, and if you want to just play a fun game you can,” she adds.

“But in order to achieve certain goals in a game, you always have to do and learn certain things.”

In Relooted, briefings about the artefacts are part of Nomali’s mission.

Players also have the option to spend time learning more about the objects, their symbolism and the communities they belong to in the Hideout Room – which is modelled on the real Northcliff Water Tower overlooking the city of Johannesburg.

“I’m fairly certain that anyone who plays the game will come away with a new perspective,” Ncube says.

“Whether it’s about an unknown history, injustices that people are still waiting to be addressed or even the fact that people in Africa can make games that are at a global standard.”

You may also be interested in:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC